Want to Know if You Are Hypermobile? Click Here to Read Part 1

In Part 1 of this blog: “Am I Hypermobile and Why Should I Care?” I presented a standard test and some criteria to help you determine where you or your clients fall on the Hypermobility spectrum. If you scored a 5 or more on the Beighton Score, or if you are just dealing with some “wonky” joints … there are some things you can do to help.

Remember:

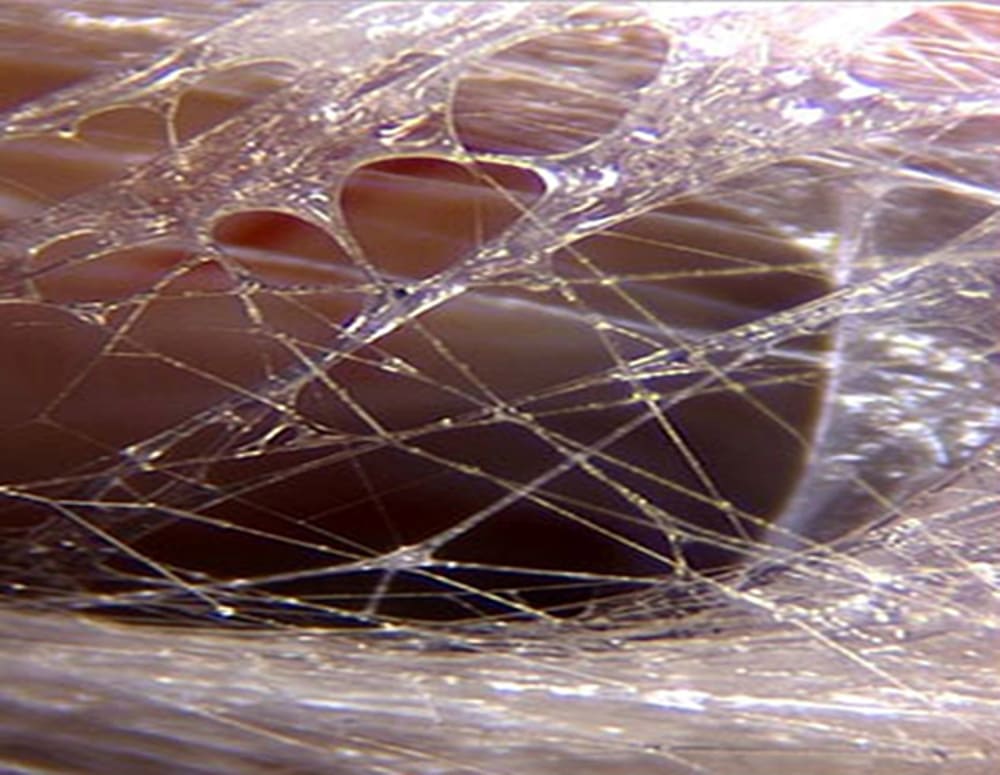

- Hypermobility is a connective tissue disorder affecting the soft tissues of the body, making the ligaments and tendons of each joint softer and less efficient than they should be.

- Hypermobility should not be confused with flexibility which refers more to stretchiness of the muscles — not the joints. Another term for loose joint is Hyper-laxity.

- If you fall on the spectrum, you may be experiencing a long-list of symptoms which often appear unrelated and involve many systems of the body including musculoskeletal, nervous, digestive, circulatory; plus internal organs and skin.

- Many of these symptoms are hard to diagnose or often misdiagnosed. There is currently no blood test or marker for hypermobility … and often multiple issues are treated separately by different doctors and never related to each other.

Those affected with more serious illnesses like Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), Marfan’s Syndrome, & Osteogenesis Imperfecta will need to seek medical attention — but seeking help from a movement specialist like a Pilates Teacher, Personal Trainer, Physical Therapist, etc. can help you address joint hyperlaxity by teaching you how to strengthen, stabilize, and organize joints for optimum efficiency and safety.

Understanding Joints

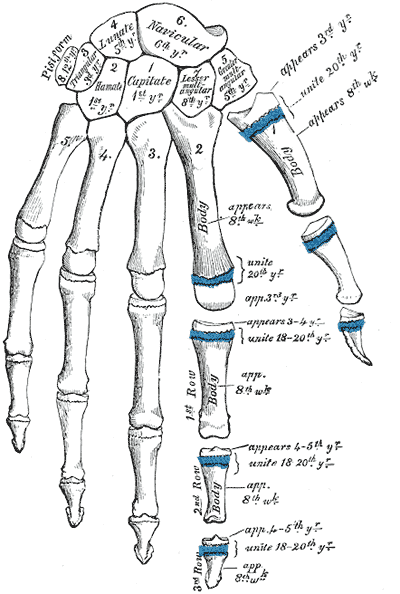

Hypermobility Syndrome (HMS) is a connective tissue disorder affecting collagen. Our connections — or joints — are made up of bones held together by ligaments, tendons, bursa, fascia, and muscles — all built from collagen!

Bones …

- are responsible for locomotion, but do not move themselves

- have ready-made attachment points for connective tissues that hold them together

- move against and around each other but rarely touch

- have no contractile properties but can re-grow

Ligaments …

- connect bone to bone

- absorb external force

- are considered primary stabilizers

- are inert tissue, having no contractile properties

- cannot be strengthened, cannot re-grow

- once overstretched, cannot return (like rubber bands)

Tendons …

- connect muscle to bone

- are active tissue – can re-grow

- can be considered secondary stabilizers

- are affected by muscle movement

Muscles …

- contract and release to move bone

- are considered secondary stabilizers

- are active tissue – have contractile properties

- can be strengthened – can grow

“Ligaments are seatbelts and muscles are the brakes” from Katy Bowman, M.S., Author of “Alignment Matters” and Move Your DNA. Check out her website for books, podcasts, and a wealth of easy to understand information about all things movement.

Joint Shape Affects Mobility

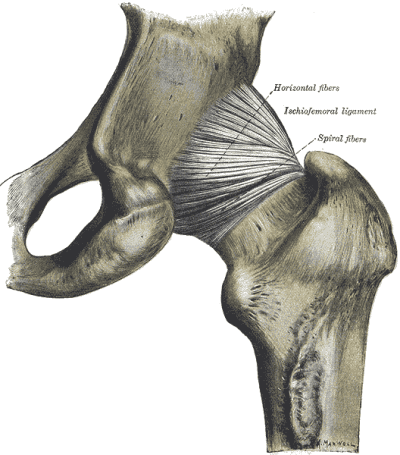

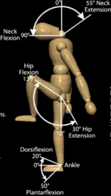

Joints come in different shapes that determine how each joint functions. Hinge joints like your knee work similar to a door hinge that only swings in two directions. Your hip joint is a ball & socket with movement in many directions.

The more moveable a joint… the less stable and the more prone to injury. Joints with the most mobility have lots of ligaments to hold them in place, and fluid filled sacks called bursae to cushion and smooth the movements — all made of collagen. Think about what this means to a body with hypermobility!

Healthy joints have pre-determined ranges of motion. A Neutral joint results when there is minimal to no tension on the connecting bones and they are resting in place. A hypermobile or hyperlax joint moves beyond the normal range of motion which makes it even more prone to instability and injury.

What About Fascia?

Much has been explored about Fascia in recent years. Movement specialists cannot ignore the role fascia plays in joint function (and dysfunction.) Should it be considered when working with joint laxity? You decide:

- Is it connective tissue?

- Is it made of collagen?

- Does it surround joints?

- Can it move? Can it be Strengthened?

- Does it stabilize?

Understanding Movement

Muscles are attached to bones by tendons. As a muscle contracts – it move bones toward each other, decreasing the joint angle. As a muscle releases, the bones move away from each other, increasing the joint angle.

Agonist/Antagonist refers to opposing muscles or muscle groups. They are often anterior to posterior (front to back) like the bicep/tricep or the quads/hamstrings.

- In Concentric or the “positive” part of a movement — where the bones are moving toward each other, the Agonist is contracting (or shortening) and the Antagonist is stretching (or lengthening.)

Try it: Contract your bicep and feel your tricep stretching. Or stand and bring your foot to your butt – this contracts the hamstring and stretches the quad. This is a useful concept and a simple technique when trying to stretch a particular muscle. - In Eccentric or the “negative” part of a movement — the bones move away from each other and the Agonist lengthens. In many cases muscles contract eccentrically to perform “braking” functions. The Pilates equipment utilizes eccentric movements since a spring needs to be closed with control.

Try it: Stand up tall and hinge forward with a flat back. In a Forward Bend, the Back Extensors are eccentrically contracting to “brake” the forward fall against gravity. - In Isometric Movement – Both Agonist and Antagonist are contracting simultaneously and the length does not change — so the joint remains still.

Shortening of muscles is good for stability of a hyper lax joint because it brings the bones together. Lengthening of muscles takes the bones away from each other, resulting in a less stable joint. Isometric movement produces no change in length but still engages muscle fibers — producing excellent stability! Wouldn’t this be helpful for a hypermobile client whose joints move too much?

Co-Contraction is when you consciously contract both the Agonist and Antagonist at the same time – producing a much more stable joint! There is no change of length and all the muscles that surround that joint are strengthening!

Try it: While standing co-contract the Quad (pick up your kneecap) & the Hamstring (draw your heel to your butt.) Do you feel stability in the joint? More importantly, did your lose your hyperextension? Is the joint in neutral?

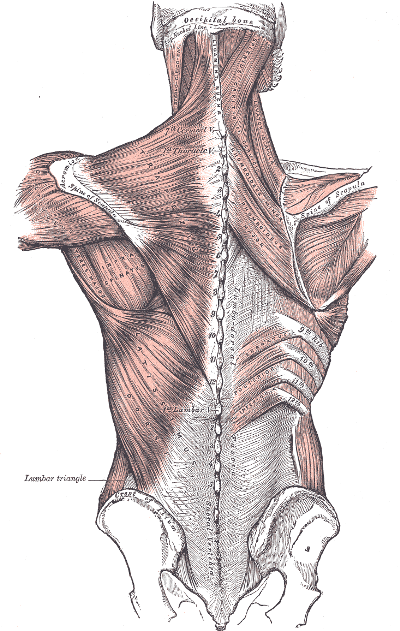

More about Muscles … How Do Muscles Stabilize?

Remember that ligaments and tendons play a role in stability … But we have no control over the ligaments and they cannot re-grow once they are overstretched. We do, however have control over the muscles. Muscles act as stabilizers in several ways:

- Can be Agonist/Antagonist, Primary Movers that “fix” a joint or…

- Can be Synergistic Muscles functioning together (ex. Serratus Anterior and Rhomboid protract and retract. By contracting at the same time they fix the scapula on the spine.) or…

- Can be Intrinsic Stabilizers — often smaller, deeper muscle groups that contract isometrically to stabilize a joint (For example the Transverse Abdominus acts like a girdle and functions more as a stabilizer than a prime mover.)

Other examples of deep stabilizers are Rotator Cuffs – whose job it is to hold the shoulder in place; Glute Medius & Minimus which act on the hip joint; and Multifidae — deep muscles in your back that connect from vertebrae to vertebrae and help to hold you up!

Open Vs. Closed?

Movement is looked at as a Kinetic Chain where one link in the chain affects the next. Movements can be classified as Open Chain or Closed Chain.

Open Chain happens when the end range or distal end is free to move and not fixed. For example if you stand up, lift your knee, and extend your leg in front of you. You are performing leg extension in an open chain — the foot is free.

Closed Chain happens when the distal end is fixed — When the muscle moves the origin rather than the insertion. For example, if you get up from a chair, your leg is performing the same movement (leg extension) but the distal end (your foot) is anchored and you are moving the other end away from the anchor. This is a closed chain movement.

Closed Chain are typically more compound movements, more stable and therefore safer; while Open Chain movements are more isolated, less stable and therefore can be less safe for a loose joint!

Your choice depends on the objective — If you’re looking to challenge stability, use open chain movements. If you’re looking to stabilize a hypermobile joint, you may want to close the chain!

For Pilates Teachers

- Leg Circles = Open Chain

Footwork = Closed Chain - Chest Press = Open Chain

Pushups = Closed Chain

Hands and feet in straps is mostly Open Chain - Hands and feet on footbar is mostly closed chain

- Try it: Which of the following three exercises is performed with a closed chain

- Arm Circles

- Long Stretch

- Chest Expansion

(Answer: Long Stretch)

What is Proprioception?

There’s one other critical piece for a hypermobile body. People who fall on the hypermobility spectrum often have problems with proprioception. This is the ability for the brain to interpret where the body is in space. A hypermobile person may be less adept at determining a safe place for each joint and is therefore more likely to go beyond the normal range of motion — possibly even subluxing a joint.

So What Should I Do?

Now that you understand joints and how they move, how do you apply this information to stabilize a “wonky” body? I have devised a set of principles that I use everyday in my own body and especially when working with hypermobile clients.

1.Strengthen Muscles that Protect the Joints

Remember that muscle moves bone and that we have little control over the weak connective tissue in a hypermobile body. So to increase the ability of the joint to absorb external forces — grow the muscles that surround and cross the joints.

- Aim for Hypertrophy (muscle fiber growth) — Listen up Pilates teachers… This is NOT a dirty word! Muscles grow stronger when they are put under load and brought to failure. This can happen with high repetition or with heavy weight. Be aware that heavy weight, low rep exercises can increase muscle mass while decreasing repetitive movement in the joint. Science shows it also increases bone and tendon growth!

- Use Concentric and Isometric more than Eccentric — because you want muscles length to shorten or stay the same.

- Compound movements put more strain on multiple joints – You may want to isolate muscles for growth!

2.Train Proprioception & Stability

Remember that hypermobile bodies typically have poor proprioception, so reign it in! Learn where neutral is for your joints and what it looks like to go beyond the normal ROM — both during exercise and in everyday activities.

Awareness is key and the number one tipoff is pain — which often comes after the movement (for example – you may not notice a hyperextended elbow while carrying groceries – until you put them on the counter and go “ouch”)

- Learn neutral for your joints and hold it there — don’t take things to the end-range. Don’t “lock out” a joint.

- Learn to co-contraction to stabilize – especially knees and elbows

- Cue the muscle, not the joint — telling a client to “soften” or bend a joint will take it out of hyperextension but does not produce a strong result in the muscles — it is not stabilizing!

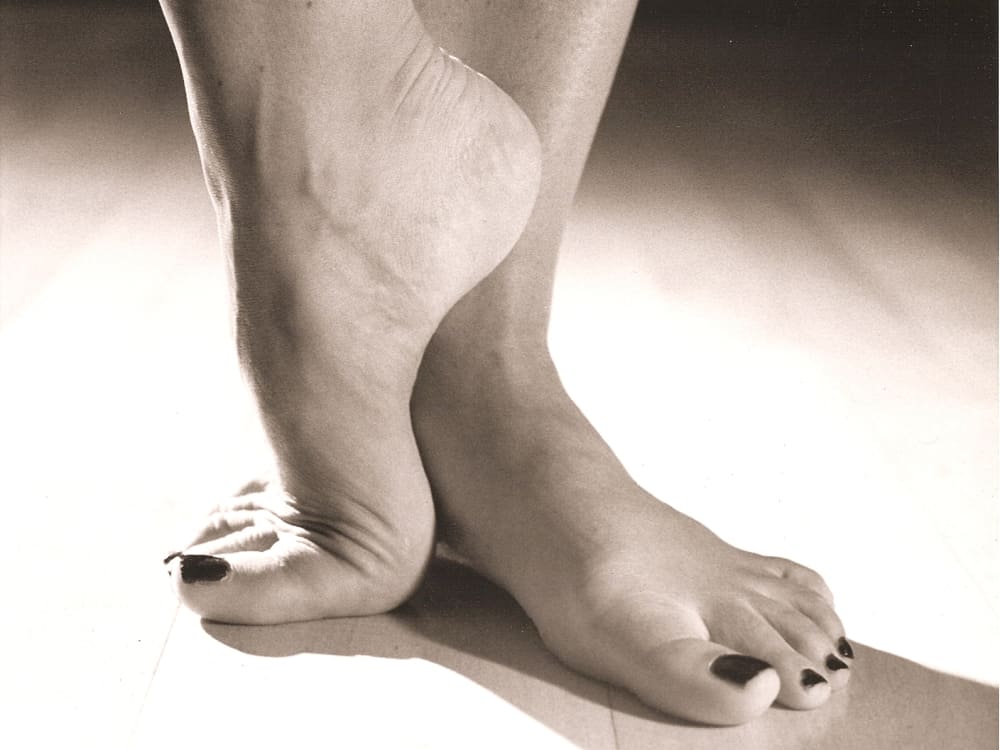

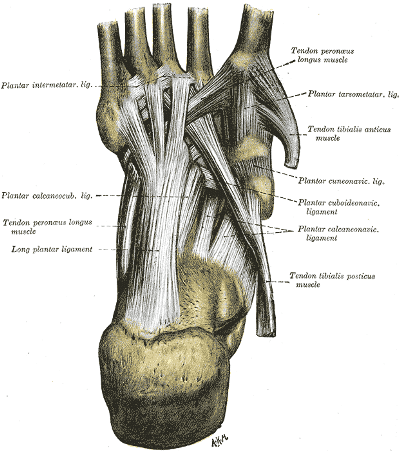

- Stop “sitting in” the joint (A good example of this is “Barbie Feet” where a hypermobile foot will sit high on the metatarsals. Lowering the heel will cause more work in the foot and leg muscles.)

- Avoid excessive forces at high velocities (e.g., running, sharp cutting sports, fast throwing, repetitive motions) Avoid twisting or torsion of a joint, especially with force — torsion forces ligaments.

- Pay attention… when you fix one joint, you may be de-stabilizing another! (ex. holding legs in Teaser or Rollup may shear the spine; Jamming the shoulders down can limit scapulohumeral rythm)

- Close the chain if needed for more stability.

Start with the Pelvis

An excellent resource for hypermobile bodies (particularly those with EDS) is Kevin Muldowney, PT, Author of “Living Life to the Fullest” from Outskirts Press.

He believes the Pelvis and SI should be addressed first since they are the body’s foundation

- Head/arm/trunk weight is 2/3 of your body weight

- The SI (Sacroiliac Joint) is responsible for transferring forces to lower extremity

- SI has no primary movers & no crossing muscles, only ligaments — the only sacrum muscles are piriformis and multifidi

3.Modify Your Approach to Stretching

Remember that Lax joints can actually mean TIGHT muscles (especially hamstrings) because the body is trying to stabilize joints that move too much. But stretching for a hypermobile person doesn’t really work because they simply move the joint instead of the muscle.

- Avoid the usual stretches. You will often see a hypermobile body perform forward bend, side splits, over-arched back, collapsed downward dog, etc. because they are good at them — but they are not getting the benefit of the stretch.

- Learn end-range and don’t go there.

- Better yet, learn to stretch the muscle belly vs. the joint. I teach my clients the origin and insertion of muscles so they can work to pull those two points apart in a stretch.

Take a forward bend for example: A hypermobile person will forward bend easily by flexing at the hip and “sitting” in the joint. To stretch the muscle belly instead — engage the back line (by drawing heels toward butt), then lift the sitz bones and draw the knee away. - Release Trigger Points instead of stretching using massage, pinky balls, foam rollers, etc.

Specifics by Joint

Learn what muscles affect what joint. Then you will know what to strengthen, what to co-contract, and how to stretch. Here’s a brief list to get you started. To stabilize the joint listed, strengthen and/or co-contract the following:

- Pelvis and Hips – Piriformis, Multifidi, Glutes & Hip Flexors

- Knees – Quads & Hamstrings

- Elbows – Biceps & Triceps, Pronators & Supinators

- Spine -(Cervical, Thoracic ,and Lumbar) – Flexors, Extensors, Rotators, Multifidi

- Ribs – Intercostals, Diaphragm

- Feet, Ankles, Toes – Calves, Shins, Plantar & Dorsal muscles

- Wrist, Hands, Fingers – Forearm Flexors & Extensors, Grip

- Shoulders, Clavicle – Deltoids, Rotator Cuffs, SCM (Sternocleidomastoid)

- Scapula – Rhomboids, Serratus

Most forms of exercise can be safe and helpful for the hypermobile client — they just need a little more awareness and a slightly different approach. I stick to 3 principles for my own hypermobile body:

- Strengthen muscles that protect the joints

- Train Proprioception and Stability

- Modify my approach to Stretching

Next time you’re in class and you see a hypermobile client make an exercise look “pretty” and they seem to perform it with ease… keep in mind that person is probably dealing with a whole set of issues that comes with having a “wonky” body.

Want to Dive Deeper?

Book a private session with one of our amazing teachers who specialize in addressing hypermobile bodies!